Spinning Into Control

April 29, 2004 Magazine WorkNew Media Professional-in-Residence at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Lecture

I am, as Sree Sreenivasan introduced me, the Hearst New Media Editor in Residence, and my residency has been made possible by a generous gift from the William Randolph Hearst Foundation. In cashing the Hearst Foundation's check, I join a noteworthy group of writers who've benefited from the departed press baron's deep pockets, a group that happens to include Benito Mussolini ... and Adolf Hitler.

Mussolini and Hitler worked part-timed as columnists for the Hearst papers in the early 1930s, writing pieces during those odd hours that they weren't spreading fascism in Europe. Hearst, who was a sometime Franklin Roosevelt supporter, paid a variety of world leaders top dollar for their views, as David Nasaw writes in his biography of Hearst, The Chief. Mussolini, a former journalist, rode the Hearst gravy train for the better part of a decade, but he irritated Hearst by insisting on filling his column with his propaganda rather than Hearst's. Often, Hearst complained that Mussolini's columns were dull--and Hearst was right. For instance, Mussolini once wrote a column titled "Mussolini Works on Farm, Visits Factories to Learn Needs of Italian Masses."

As you might guess, Hitler was a much better writer than Il Duce. His bracing and unequivocal copy made headlines ... and sometimes it instigated international incidents. Hitler eventually fell out of Hearst's favor because he couldn't meet deadlines, and was replaced in 1934 with someone who could ... that someone being ... Herman Goering.

As a writer, I'm better on deadlines than Hitler. And I'm not as dull as Mussolini. I also work cheaper than either of them. Hearst paid Mussolini $1,200 for each column, which works out to an astounding $13,660 in today's money. Because my talk is four times as long as the average Mussolini column, I hope to meet with Dean Nick Lemann after my talk and renegotiate my remuneration at the Mussolini rate.

If Hearst were alive today, I'm certain that he'd approve of the support his foundation has extended to the study of new media because he was a new media hound. Born in 1861, he was totally obsessed with the new media that emerged when he was in his 50s and 60s--the new media being newsreels and radio. In the mid-1920s, when commercial radio was just a half-decade old, Hearst was already invested, and he personally took to his radio pulpit to sermonize on the issues of the day to his listeners. He aggressively cross-promoted his newspapers with his radio stations, many times against the wishes of his newspaper publishers.

For these reasons, I believe

the old coot would have adored the Web. I'll bet that he would have

rolled his news wire, the International News Service, into a portal

and, given his Californiacentric world view, would have out-Yahooed

Yahoo and out-Googled Google. And I think he'd agree with the thesis

of my talk: That from a tiny point on the Internet just 10 years ago

the Web has spiraled out to assume the

central position in journalism for both news consumers and journalists.

It's also my assessment that Hearst would agree with me that the Web's

spinning into control has been beneficial to the art and business of

journalism.

Now, I know that these excited views about the Web and journalism may make me sound like an infotopian barking in the pages of a 1995 issue of Wired magazine. ... While preparing this talk, I walked around the house repeating my mantra that the Web has revolutionized journalism. Every time I said that, my wife would correct me to say the Web has mostly revolutionized shopping. But I'm not a barking mad infotopian, and my argument is grounded more in history than in futurism. And with that dreaded word "history," let me introduce the first of a half-dozen slides that I've prepared to illustrate how the Web spun into control.

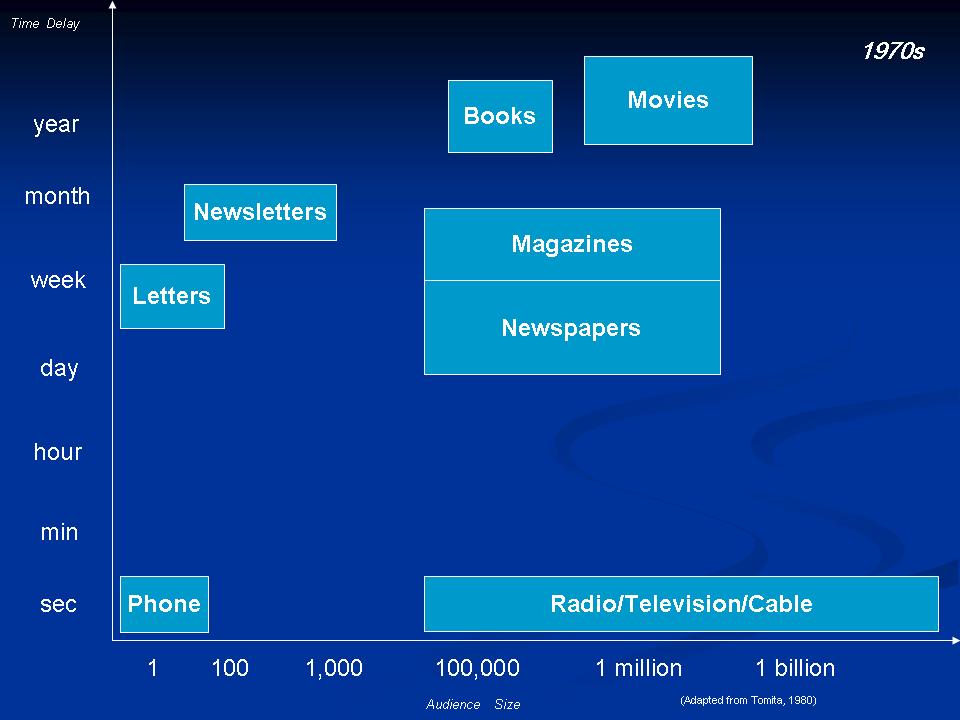

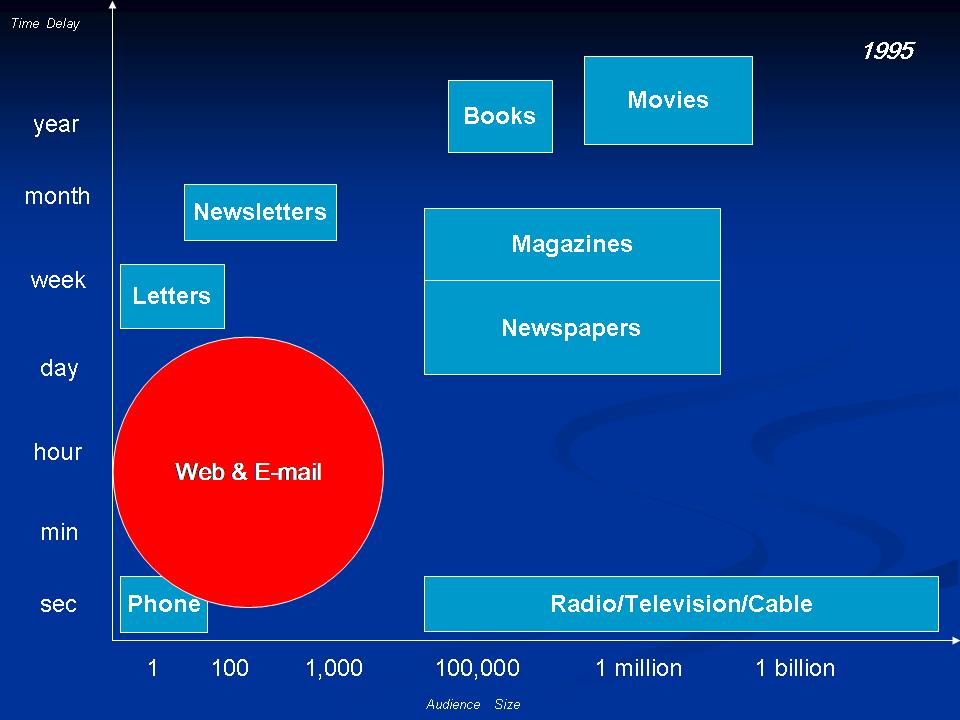

As early as 1980, more than a decade before the Web was born, media observer Tetsuro Tomita discovered what he called the "Media Gap." His now famous chart mapped existing media onto an X/Y axis, with the size of the audience running along the X axis and on the Y axis the time it took to conceive and deliver the message.

Slide 1: The Media Scene, 1970

Near the origin, he plotted

face-to-face conversations and phone calls as examples of messages with

tiny audiences that are instantaneous. Moving out the X axis, you find

similarly instantaneous messages, but these reach tens of thousands,

millions, and even billions via radio and television. Climbing the Y

axis from the origin, we bump into those small-audience media whose

messages take a few days to reach their intended: postal letters, handbills,

and newsletters. Media reaching audiences of tens of thousands or millions,

but taking a day, a week, or a year to arrive include newspapers, magazines,

books, and movies.

Slide 1: The Media Scene, 1970

Near the origin, he plotted

face-to-face conversations and phone calls as examples of messages with

tiny audiences that are instantaneous. Moving out the X axis, you find

similarly instantaneous messages, but these reach tens of thousands,

millions, and even billions via radio and television. Climbing the Y

axis from the origin, we bump into those small-audience media whose

messages take a few days to reach their intended: postal letters, handbills,

and newsletters. Media reaching audiences of tens of thousands or millions,

but taking a day, a week, or a year to arrive include newspapers, magazines,

books, and movies.

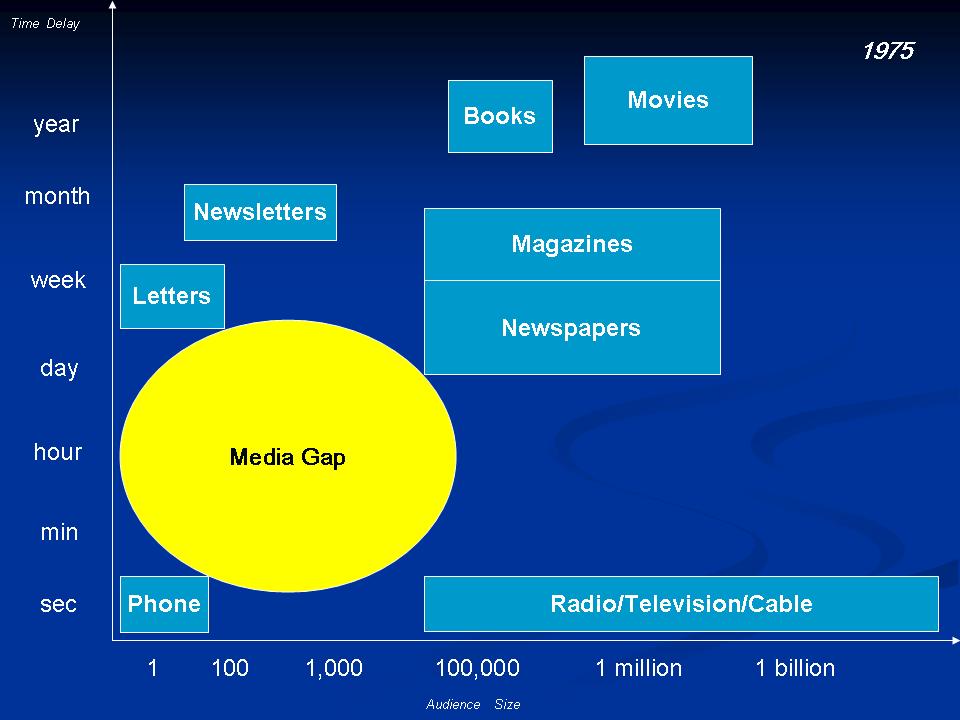

As Tomita populated the chart with the various existing media, an underserved zone emerged, one he called the "Media Gap." In another context, you might call this the "Peace and Quiet Zone."

Slide 2: The Media Gap, 1975

Why was there a Media Gap?

The simple answer is that no affordable technology existed to fill it.

Theoretically, you could print and distribute newsletters on an updated,

hourly basis to plug the gap. Or, you could hire a hundred telephone

operators to make a thousand telephone phone calls inside a half-hour.

But neither alternative was economically practical, so the Media Gap

stayed silent.

Slide 2: The Media Gap, 1975

Why was there a Media Gap?

The simple answer is that no affordable technology existed to fill it.

Theoretically, you could print and distribute newsletters on an updated,

hourly basis to plug the gap. Or, you could hire a hundred telephone

operators to make a thousand telephone phone calls inside a half-hour.

But neither alternative was economically practical, so the Media Gap

stayed silent.

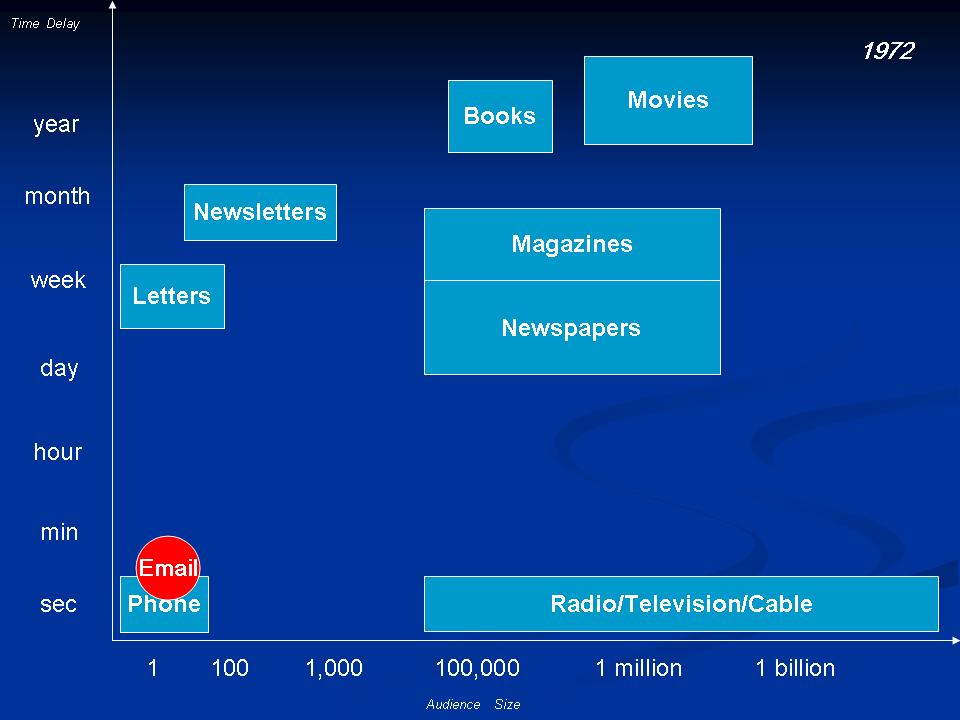

It's into this gap that the early e-mail messages flowed--cheap messages that could travel almost instantaneously to hundreds of recipients. Ray Tomlinson takes credit for sending the very first e-mail in 1971 from one computer to another in the same room, but he did it the hard way--though the Arpanet, the early Internet. Tomlinson says it was a nonsense message like "quertyuiop," but he doesn't remember for sure.

Slide 3: E-mail enters the Media Gap

Slowly, e-mail began to colonize

the Media Gap, a process that sped up with the advent of personal computers

in 1979 and the establishment of commercial e-mail services. Usenet discussion threads in the early 1980s,

where vibrant discussion groups of politics, culture, and computers

convened and thrived, filled gaps in the Media Gap, and presaged the

content of the Web.

The first Web pages arrived

around 1991. By the end of 1993, only a few

hundred Web sites

built by academics, government, businesses, and the curious existed.

The potential world-wide audience couldn't have been more than a million,

if that. But the Web was superbly adapted to grow in the Media Gap because

it could serve small audiences quickly and cheaply. And it could scale--that's

computerese for super-sizing itself--very efficiently.

Slide 3: E-mail enters the Media Gap

Slowly, e-mail began to colonize

the Media Gap, a process that sped up with the advent of personal computers

in 1979 and the establishment of commercial e-mail services. Usenet discussion threads in the early 1980s,

where vibrant discussion groups of politics, culture, and computers

convened and thrived, filled gaps in the Media Gap, and presaged the

content of the Web.

The first Web pages arrived

around 1991. By the end of 1993, only a few

hundred Web sites

built by academics, government, businesses, and the curious existed.

The potential world-wide audience couldn't have been more than a million,

if that. But the Web was superbly adapted to grow in the Media Gap because

it could serve small audiences quickly and cheaply. And it could scale--that's

computerese for super-sizing itself--very efficiently. With land-rush fervor, Web enthusiasts quickly settled nearly every pixel in the Media Gap between 1993 and 1995, building thousands and thousands of Web sites devoted to science, news, business, the arts, trivia, and, of course, pornography.

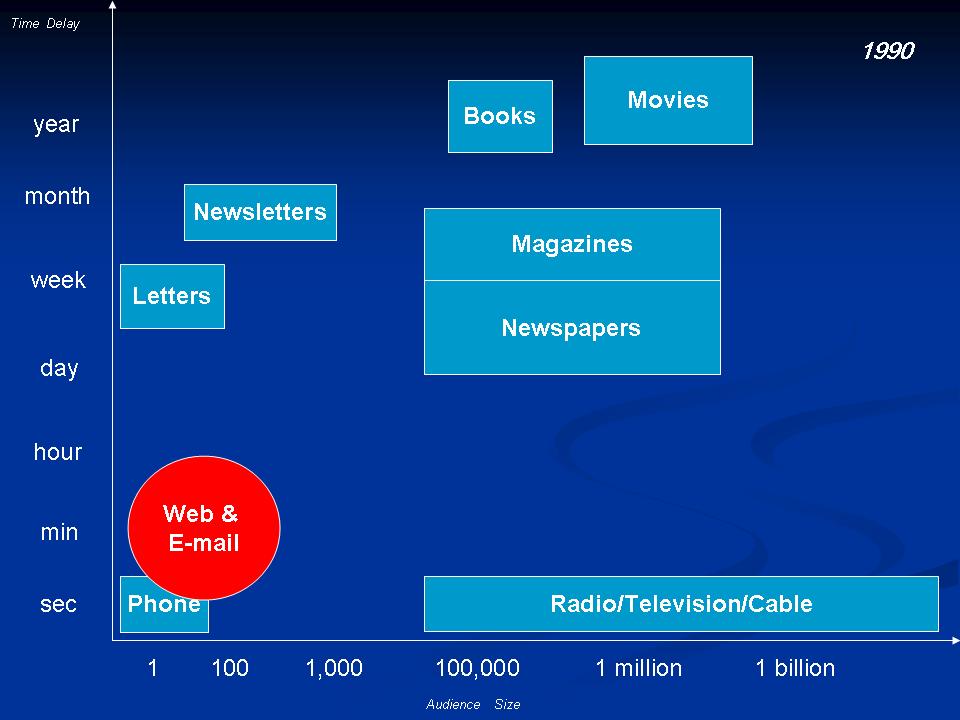

Slide 4: The Web Crowds Its Way In

Old media was

quick to cross the border and settle the Media Gap from the other direction.

Forward-thinking publishers at the San Jose Mercury-News,

Wired magazine, and Time-Warner all lit up commercial journalism

sites in 1994. Back then, most surfers connected with 14.4 baud modems.

At that speed, Web pages loaded slower than ice melts, but it was still

a glorious experience. By mid-1996, when Slate, the Web

site I work for, jolted to life, nearly every legacy media organization--newspaper, magazine, local

radio and television station, television network, branch of government,

and major company had staked a place on the Web.

Slide 4: The Web Crowds Its Way In

Old media was

quick to cross the border and settle the Media Gap from the other direction.

Forward-thinking publishers at the San Jose Mercury-News,

Wired magazine, and Time-Warner all lit up commercial journalism

sites in 1994. Back then, most surfers connected with 14.4 baud modems.

At that speed, Web pages loaded slower than ice melts, but it was still

a glorious experience. By mid-1996, when Slate, the Web

site I work for, jolted to life, nearly every legacy media organization--newspaper, magazine, local

radio and television station, television network, branch of government,

and major company had staked a place on the Web.

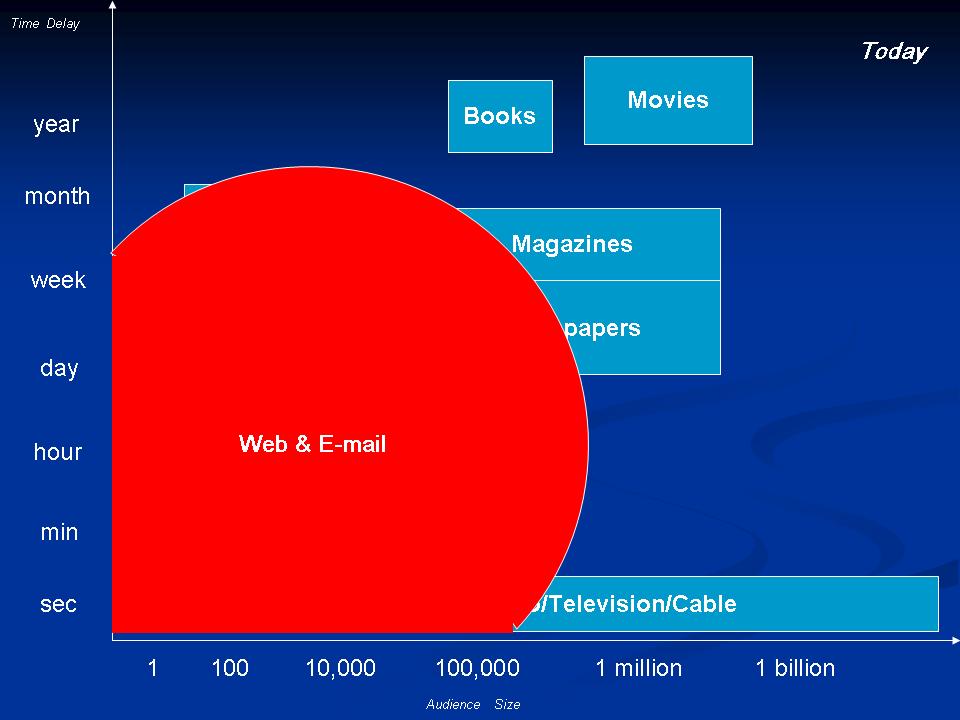

Slide 5: Media Free-for-all

Pure editorial sites

like Salon, Feed, and Word

blossomed. According to one authoritative estimate, there were about 500,000 Web sites

in the middle of 1996. Today there are upwards of 45 million and Google's

spiders have recently indexed 13 billion pages.

Slide 5: Media Free-for-all

Pure editorial sites

like Salon, Feed, and Word

blossomed. According to one authoritative estimate, there were about 500,000 Web sites

in the middle of 1996. Today there are upwards of 45 million and Google's

spiders have recently indexed 13 billion pages. The Web hinted a couple of

times in the late 1990s of its future as the journalistic center. On

the last weekend of August 1997, when Princess Diana died, millions

of TV viewers dissatisfied with what the networks were broadcasting

surfed to news portals such as MSNBC.com. For the first time, demand

for Web news exceeded Web capacity and the servers crashed. They crashed

again on Sept. 9, 1998, as millions of readers who wanted to know what

the Starr

Report said, not

what the press said it said, downloaded the full text. But Web journalism

remained a supplementary, not a primary, read for most news consumers.

I date the end of the first Web generation to the dot-com bomb of early 2000. Up until that point, the popular view was that the Web was poised to destroy the newspaper, TV, and book industries. Some of you may recall that novelist Michael Crichton famously predicted in 1993 that the New York Times and the TV networks would "be gone within 10 years." The replacements would be artificial intelligence agents downloading information based on the individual's interests and creating custom front pages and newscasts. If you haven't noticed, the Times is still here, and so are the networks.

With the crash of 2000, Web publishers pulled in their ears a bit, hoping mostly to survive. Some of the Web's journalistic glow returned during the recount hell of the 2000 presidential election, and much more returned in the weeks following 9/11.

By the time the United States

invaded Iraq in March 2003, the Web assumed the kind journalistic centrality

that CNN enjoyed for a few weeks during 1991's Gulf War. Tuning in

to CNN--the only 24-hour cable news channel at the time--was the best

way to stay informed. Even when there was no new news from the Middle

East, attentive viewers left CNN running at low volume in the background

... the way a little kid leaves a nightlight on in his bedroom for security.

If you watched CNN late enough into the evening, the Page One headlines

printed in New York Times and Washington Post the next

day were already yesterday's news to you. CNN's big day lasted only

a month or so, and soon the media center gravitated back to newspapers.

The Web's big day is now

going on its second year, and shows no sign of disappearing. For the

hardcore news fanatic who has to know the latest, the Web browser has

supplanted the cable box. During the invasion, I kept Google News up

in one window, CNN.com and MSNBC.com in another, and my favorite blogs

and newspapers in a couple more. At midnight, I read tomorrow's news

from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the

Los Angeles Times, having already consumed the leading European

papers earlier in the evening. I subscribed to e-mail lists that did

my news tracking for me and kept an Internet messenger window open to

ping friends back-and-forth with hot news tips. And whenever I needed

another wave of breaking news, I hit my browser's refresh button.

Sometimes I even got some work done for Slate.

Key to the rise of the Web

was the increase in the number of users on a broadband connection. According

to the Pew

Internet Project,

21 percent of all Internet users now have broadband at home, and 55

percent of all Internet users have it either at work or home. That number

is likely to rise, because 77 percent of Americans say broadband is

available in their neighborhoods.

The "always on-ness" of

broadband has had a transformative effect on the media habits of these

users, increasing the amount of time they spend on the Web and the number

of sites they visit. Broadband users tend to be younger and better educated

than the population at large. They tend to cut back on TV viewing, they

tend to stay at home to shop, and they tend to create or share content--blogs,

Web pages, photos, news stories, and music files--with other users.

At least three things give the Web a leg up on other media: 1) its immediacy; 2) its universality, by which I mean that 99 percent of the Web that I visit, you can visit, too; and 3) its foundation as a two-way communication medium. Newspapers and magazines determine what letters to publish in response to their stories. The Web allows readers to comment at will.

At this juncture, it seems that the Web's tentacles have spiraled out of the Media Gap to encroach upon every settled media continent. Thanks to the Web, the phone rings less often. Thanks to the Web, nobody sends postal letters if they can avoid it, ending a thousand-year-old tradition. Thanks to the Web, a significant publishing category--pure smut represented by Penthouse and Screw--has been decimated. (I'm undecided whether the decimation of print pornography by Web pornographers is a good thing, a bad thing ... or neither. But I think it's a harbinger of things to come for the magazine industry.) The television industry rightly believes that the Web is poaching their viewers, especially younger ones, the music industry blames the Web for its woes, and Hollywood fears it, too.

Slide 6: The Web Spins Into Control

What makes the Web so unstoppable--and

I'm indebted to media scholar W. Russell Neuman for this insight--is

that it's become the uber distribution channel. In the

old analog days, magazine distributors, newspaper distributors, music

distributors, and movie distributors never bumped directly into one

another. But during the past two decades, all the analog media--photographs,

audio recordings, videotape, newspaper and magazine layouts, movies,

radio, telephone, and television--have gone digital. The practical

effect of this transformation is that every digitized media can flow

through the Web into homes and offices. So when I say the Web has become

central to journalism, I'm also saying that practically all old media

has become--or is in the process of becoming--Web media. Newspaper

reporters and television producers may think

they're still newspaper and TV guys, but if you dissect their work

they're really Web journalists.

Slide 6: The Web Spins Into Control

What makes the Web so unstoppable--and

I'm indebted to media scholar W. Russell Neuman for this insight--is

that it's become the uber distribution channel. In the

old analog days, magazine distributors, newspaper distributors, music

distributors, and movie distributors never bumped directly into one

another. But during the past two decades, all the analog media--photographs,

audio recordings, videotape, newspaper and magazine layouts, movies,

radio, telephone, and television--have gone digital. The practical

effect of this transformation is that every digitized media can flow

through the Web into homes and offices. So when I say the Web has become

central to journalism, I'm also saying that practically all old media

has become--or is in the process of becoming--Web media. Newspaper

reporters and television producers may think

they're still newspaper and TV guys, but if you dissect their work

they're really Web journalists. For those who worry about media

consolidation, the digital revolution and the Web have placed the old

medias of newspapers and television into direct competition inside the

Web space. And that competition is now world-wide. The New York Times,

the Los Angeles Times, and the Washington Post,

which once had a lock on international coverage in the U.S., have seen

their lock broken. Readers now have real-time access to the foreign

press and translation services. If you don't admire the work of Judith

Miller, Robert Fisk is only a click away.

In Webifying themselves, broadcasters,

newspapers, and magazines have conceded the Web's journalistic centrality,

which is the best endorsement of my thesis that I can cite. TV news

routinely refers viewers who want the complete story to visit their

companion Web sites for news updates, graphics, maps, analysis, opinion,

and transcripts. More and more, they're offering the crown jewel of

video. Newspapers and magazines publish many of their best breaking

stories on the Web before printing them on paper. And nearly everything

you hear on NPR can be downloaded from the Web, which makes you wonder

if NPR is a broadcaster with a Web site ... or an audio Web site that

also broadcasts. My friend David Corn, Washington Editor of The Nation,

says that inside his magazine, he proselytizes that The Nation

should think of itself not as a magazine, but as an idea--and idea

that can best manifest itself on the Web.

As the Web has been spinning into control of readers, it's also been spinning into control of newsrooms. Journalists, who've enjoyed access to broadband Internet connections for longer than most readers, have fully incorporated the Web into their professional habits. Not that long ago, reporters relied on yellowing clip-files maintained by newsroom librarians for the back story. That changed in the late 1970s, as Lexis-Nexis became the preferred shortcut for reporters who needed to come up to speed. Today, the research might of the Web has made the newsroom librarian an endangered species. With the exception of breaking news like 12-car freeway pile-ups, the first stop in the reporting of most news stories in any journalistic medium these days is a Web search. As deadline approaches, journalists continue to consult the Web for access to leads, Google up authoritative sources, conduct e-mail interviews, download official documents, check facts, and size up the competition's work.

The Web makes possible deeper, more substantive, and more timely work. It's also accelerated the pace of journalism, much in the way the cell phone, the personal computer, the desk telephone, and the typewriter did before. If you asked reporters which they'd surrender first, their Web connection or their telephone, I'd wager that most would hand you their phone. The Web also frees pure Web journalists from the arbitrary deadlines of press time and broadcast slot. The Web lets stories roll when they're ready to roll.

Some complain that the Web has made journalism less accurate. Obviously, some Web sites are founts of foolishness and journalists should apply the same skepticism to them as they do to human sources. But inaccuracy has plagued journalism from the start. As Oscar Wilde liked to point out, journalism's highest purpose is keeping us in touch with the ignorance of the community. But as a lifetime binge-eater of news and full-time press critic, it's my anecdotal observation that the Web has increased both accuracy and accountability. The Web makes it very difficult for reporters to hide their weaknesses. There's always somebody looking over your shoulder, evaluating and correcting you. As Web reporters can testify, readers don't let you off lightly when you make a mistake. The rotten bastards comb through your copy looking for the tiniest goofs and grammatical slips, then they bomb your e-mail address with their findings. For the journalistic priesthood, which has deliberately barricaded itself from readers with security guards at the door and screening devices like caller ID and voice mail, the scrutiny of the Web is something that has actually increased accuracy.

The Web has the potential to improve journalism by exposing reporters to a new constellation of sources. My public e-mail address has become an important place to collect tips and engage in water-cooler conversation about news and events. If you chose your e-mail correspondents carefully, you end up recruiting scores of unpaid but tireless research assistants. Every day a couple of readers point me in directions that I follow.

The Web's democratizing effect should not go unmentioned. Fifteen years ago, only the journalistic priesthood had affordable access to electronic news databases, comprehensive sets of newspaper clips, up-to-date encyclopedias, and reverse phone directories. Today, a smart amateur can accomplish more searching Google in five minutes than an expert reporter from the 1970s could do in a day. Many times, the only thing a reporter from the New York Times has over one of these newcomers is the undeniable power that comes from saying, "I'm a reporter with the New York Times."

The Web has ascended, in part,

because of the dramatic way in which it has driven down the cost of

transmitting words, sounds, and images. We don't think about how expensive

it used to be to transmit words, but we should. In the late 1800s, for

example, trans-Atlantic telegrams cost $50 or $100 in today's money

to send 20 words. These prices spurred the invention of the abbreviating

language of telegramese to compress complex messages into a few words.

Telegram writers added the prefix "un" to any word to amend the

meaning of "no" or "not" to a word. This technique is illustrated

by the famous, if apocryphal, exchange of telegrams between a foreign

editor and his lazy reporter in the field. "Why unnews?" the editor

telegrammed to his reporter, who hadn't filed for weeks. The reporter

replied, "Unnews good news." The editor retorted, "Unnews unjob."

We still use a kind of telegramese to message each other on cell phones, but when was the last time you used telegramese in an e-mail or a Web page to save money? Not long ago, the technological constraints were such that no media company could have delivered blog-size editorial in real time to a big audience at any price. Today, your kid sister in middle school can afford one. By collapsing the costs of communications, technology has made possible the indisputably journalistic world of the blogosphere, one of the prime tenants in the former Media Gap.

In the language of economics,

the Web has lowered the barriers of entry to those who want to practice

journalism. Blogs now radiate from every segment of the political spectrum,

improving the quality of the national argument. The better known sites

are Kausfiles, Instapundit, Talking Points Memo, Altercation, Atrios,

AndrewSullivan.com, the Volokh Conspiracy, and the Daily Howler. Most

of the popular blogs are sole proprietorships, unsupported by media

companies, and they've demonstrated an ability to break news. Last

week, for example, thememoryhole.org broke a big story that had eluded

the media by getting Defense Department photos of the coffins returning

from Iraq after filing a FOIA. Any news organization in the country

could have done this, but only a Web site actually thought of doing

it.

Other Web sites that capitalize on the low costs of the new technology include the news aggregators. These sites digest and assess headlines from around the world. The granddaddy of the aggregators, of course, is the Drudge Report, which even breaks news from time to time. Others aggregators include the Command Post, Common Dreams, NewsMax, TomPaine, BuzzFlash, and Free Republic, some of which post original content. Services such as AmphetaDesk and Google News do similar labor with no or little human intervention, leaving the heavy lifting to robots.

In spinning into control, the Web isn't eliminating old media. History shows us that most new media is additive, and rather than extinguishing existing media, it forces existing media to change. (The only extinct journalistic form I can think of is the movie newsreel.) So I don't expect newspapers, magazines, radio and television, books, postal mail, or the plain old telephone line to disappear any time soon. But just as radio required newspapers to rethink their mission, and television required radio to rethink its, the Web is forcing every media player and every media wannabe to rethink their place in the media map, and to fulfill news needs we didn't know we had.With all this good news to

share and all my upbeat enthusiasm for the Web, I'd like to leave

you on a downer note. As a research tool, the Web is woefully incomplete.

Sources that have yet to be digitized--such as most pre-1980 publications--aren't

widely available on the Web. If journalists rely on only digitized sources,

their work will have an enormous blind spot. So don't throw away your

telephones, don't sell your books, don't purge your mind of your

liberal arts education, and don't ever give up face-to-face interviews.

Another disturbing development is the removal of public information in the name of the war on terror. Yet another is the distinct possibility that Internet service providers, eager to concentrate eyeballs in a place they can make money, will wall off parts of the Internet. study also cites a move afoot by some Internet service providers to block customers from operating Web sites. In unfree countries, "filtering" technologies are used to block users from controversial Web sites. As the war on terror and the war on file-sharing escalate, the U.S. could become one of those unfree countries. The "two-wayness" of the Web is one of its greatest attributes, and it would be a tragedy if the government and industry reconfigured the Web platform to allow authorities to police media and control the creation of new media.

My darkest thought is that

in creating one universal platform for journalism we may have inadvertently

created a medium that is easier for government and corporations to control

and censor. It would be a fine folly to have created such a technology

of freedom only to have it fall into the hands of people like Mr. Hearst's

columnist--buddies--Benito and Adolf.